Special Autonomy Grant Effectiveness in Papua and West Papua

by: Didik Purwandanu, PATTIRO’s Senior Program Manager of Social Accountability

Background

“..However, PEPERA is not our final destination. The most important thing is the development of West Irian simultaneously and within the context of REPELITA implementation… Like any other regions, West Irian will get its place as a level I Region with autonomy that is real and broad…”

(part of state speech by the President of the Republic of Indonesia General Soeharto in front of House of Representatives Gotong Royong on 16 August 1969).[1]

Background Snippet Video and Opinions About this Policy Memo:

Forty-three years since referendum (PEPERA or Penentuan Pendapat Rakyat) held, autonomy that was promised by the Government of Indonesia eventually implemented after the enactment of the Law No. 21/2001 on Special Autonomy (Otonomi Khusus/Otsus) for Papua Province. In the law, Otsus is defined as a special authority that is recognized and granted to Papua Province (Previously named West Irian) to manage and administer the interest of local community according to its own aspiration and basic rights of Papua community.[2]

Based on this regulation, Otsus includes several things particularly: firstly, authority arrangement between the Government of Indonesian and the Papua Provincial Government and its implementation that is done distinctively; secondly, recognition and respect for basic rights of the native Papuans as well as strategic and fundamental empowerment; and thirdly, to establish good government that is characterized by:

a. participation as much as possible in planning, implementing and monitoring the government through active participation of tribe/community elders, religious leaders and women;

b. development implementation that is directed to fulfill the needs of native Papuans in particular and Papua Province residents in general and still adhered tothe principles of environmental conservation, sustainable development, fairness and directly beneficial to the community;

c. furthermore, a transparent and responsible government and development implementation.

Fourthly, firm and clear separation of authority, duty and responsibility among the legislative, executive and judicative bodies, and also the Papua’s People Representative (Majelis Rakyat Papua/MRP) that is granted specific authorities to represent the culture of natives.[3]

The source of funds for Papua and West Papua Provinces (West Papua Province was originally part of Papua Province) is regulated in Law No. 21/2001. Firstly, in the case of fund balance, as mandated by Law on Otsus, Papua and West Papua Provinces will receive preferential treatment in profit-sharing from natural resources of oil and gas, which is 70%. Meanwhile, for other natural resources, both provinces receive the same percentage as other provinces. For profit-sharing from Property Tax (Pajak Bumi dan Bangunan/ PBB), both will receive 90%. From Customs Revenue of Right of Property they will receive 80%, and from Personal Income Tax (Pajak Penghasilan Orang Pribadi/ PPh) they will receive 20%.[4]

Secondly, there is a special revenue for Otsus implementation that amounts to 2% of National Intergovermental Transfer Grant, as we know is called Otsus grant. Thirdly, there is an additional grant of infrastructure development. Second and third revenue is valid for twenty years and will be zero thereafter. Specifically for preferential treatment of oil and gas profit-sharing, it will be 50% after twenty-five years.

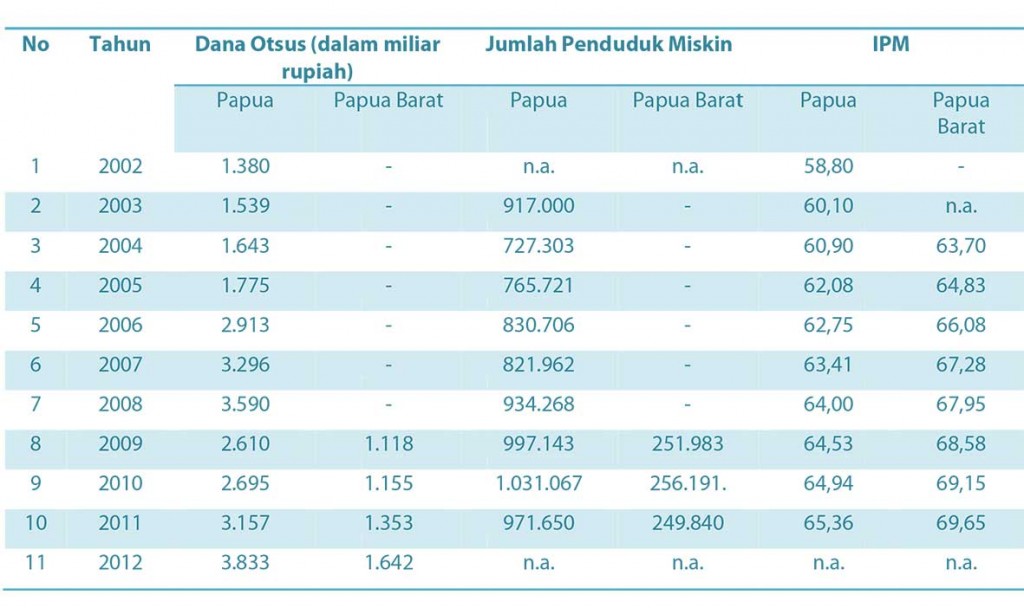

Throughout 2002 and 2012, Papua Province received IDR 28.445 trillion of Otsus grant and IDR 5.271 trillion of infrastructure grant. West Papua Province, which has been established since 2008, has received IDR 5.409 trillion of Otsus grant and IDR 2.962 trillion of infrastructure grant.

Fourthly, Intergovernmental Transfer Grant as a block grant from central government is used to equalisation scheme between regions. Analysis conducted by the World Bank shows that in addition to preferential treatment with the existence of Otsus grant, special infrastructure fund, and fund balance, Papua’s Intergovernmental Transfer Grant itself is already large. In 2005 for example, its amount reached 25.5% of national revenue or about IDR 88.8 trillion. So it is not surprising if compared to other regions, Papua at the time already received five times more than that of East Java and four times more than that of West Nusa Tenggara.[5]

Otsus grant effectiveness

What is the impact of Otsus grant for the welfare of the community in Papua and West Papua? In terms of implementation, there is an increase in school enrollment rates, literacy rates, average enrollment in school, addition of health infrastructure and medical personnel, and also a decrease in poverty rates. In 2011, there was 31.98% of poor people in Papua, and 28.2% in West Papua. But according to West Papua Governor Abraham Atururi, even though there is a decrease in poverty rates, West Papua is still the second poorest province in Indonesia. Open unemployment is still around 5.5%, even though it has decreased compare to 7.73% in 2009. Looking at the trend of poverty rates at table 2, it can be seen that Otsus grant did not give any significant impact.

![Table 2 Poverty Percentage in Papua and West Papua [6]](https://pattiro.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/t2-1024x599.jpg)

Meanwhile, the second one is at the policy implementation level. According to Djohermansyah, it is seen in the lack of public understanding for Otsus implementation, limited Otsus’ quantity and quality implementation, MRP that is still loosely interpreted, and the minimal effort by Local Government in implementing Otsus. Therefore, in the future the Ministry of Home Affairs through Directorate General of Regional Autonomy will evaluate Otsus implementation annually.

Initially, Otsus was very supported by policymaker in Papua, as reflected from Papua’s Governor at the time, JP Salossa, “about 75% of Papuans is believed to still live under the poverty line as a result of a limited sea, land and air transport facilities and infrastructure in the area. Transportation facilities and infrastructure in Papua greatly affect the lives of people in Papua.” The Governor is optimistic that the implementation of Law on Otsus, that it can improve the people of Papua and reduce its poverty rate.[8]

Unfortunately, as explained in table 3 that compares Otsus grant allocation with poor residents and human development index, the allocation is not capable to lift them up significantly. Instead of improving, the number of poor people is still high and human development index is still far below the national average, which is 72.

Why ineffectiveness happen?

We summarized from several evaluation and research results, and concluded three main factors for ineffective management:

1. Lack of public participation. One of the indicators is civil society access to public document related to planning and budgeting in Papua and West Papua. On the one hand, Otsus gives chance for the MRP, but they must be given more role in facilitating civil society to get their rights to public information. Transparency principle in good governance supposed to be giving chances for the community to be involved in monitoring public service to be better. This participation will verify public service quality and to increase the sense of belonging of the community to the development result. Nonexistent data that can be accessed by civil society and even the central government will result in follow up question of how Otsus grant is managed by the Papua and West Papua government and can it be accountable? It has been indicated that there is a mismanaged Otsus grant of IDR 4.12 trillion[9] as found by National Audit Board (Badan Pemeriksa Keuangan/BPK), therefore, transparency aspect needs to be prioritized.

2. Transfer mechanism without specific pre-conditions. Finance Minister Regulations regarding the amount of annual Otsus grant for Papua and West Papua does mention its priority to be used for education and health, but it does not mention specific preconditions to prevent local government getting easy transfer of fund. In total, it also shows a significant increase. Experience in various places and both in developing and developed countries show that non-preconditions transfer tend to be disincentive because it makes local government to depend on that fund rather than on local revenue. Further impact is the condition of fiscal illusion, where this special transfer fund is unable to improve local economy and until its twenty-five years time, it has the potential that both provinces will still depend on the budget from central government.

3. Coordination across Ministries or Agencies in monitoring needs to be improved. One indication is that each ministry or agency to do separate monitoring and evaluation for different interest. Ministry of Home Affairs regularly evaluates Otsus implementation, cooperates with non-government organization. Other example, monitoring and evaluation for Health Minimum Service Standard (MSS), where the number of regency in Papua and West Papua that submits report is less than 15%, far below other provinces where the majority of them already reach 100%. Data shows that for several years up until 2010 and 2011 there is no significant improvement, even then the validity of data cannot be guaranteed. In a logical framework, it is expected that achievement at the HDI level can be reached if medium achievement, which is MSS achievement target, can be reached.

Recommendation

- Central and local government need to ensure a wider space for community participation in planning, budgeting and monitoring Otsus grant. This participation is parallel with central government’s effort in ensuring freedom of public information. Community participation is done to measure three things in each of implementation stage, namely: (a) effectivity, or how far the program using Otsus grant can benefit the community; (b) obligation to procedure, or is there any sanction for fraud or mismanagement; and (c) access, or if the community is able to access important information if needed. MRP needs to take a strategic role in facilitating civil society in monitoring every stage of the program.

- Improvement of transfer mechanism.Central government needs to formulate improvement of transfer mechanism from non-preconditions into preconditions. Preconditions to be used are formulated gradually according to situation in Papua and West Papua as it requires affirmative policy. For example, in the first year central government required MSS of education and health monev reporting of at least 70%, and the second year, target is increased to be 100%, and for the third year and next related to data validity. It can be added in the last three years of Otsus, MSS achievement preconditions are enforced.

- Coordination across Ministries or Agencies in monitoring and evaluation, particularly among Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Education and Culture, Ministry of Health, National Audit Board (BPK), Finance and Development Supervisory Agency (Badan Pengawas Keuangan dan Pembangunan/BPKP), and Ministry of Administrative Reform. Central government can also form a team across ministries or agencies in monitoring and evaluating program and use of Otsus grant and associated with preconditions in changing the transfer mechanism. Any problematic findings should be investigated, so that there is no saying of “Otsus grant need not to be investigated since it is a donation from Indonesia so that Papua does not need to be independent.”

[3] Agustinus Fatem, “Sebelas Tahun Implementasi Kebijakan Otsus di Tanah Papua: Isu, Target, dan Upaya

Perbaikan”, Jurnal Ilmu Sosial, Vol. 10, No. 3 Desember 2012.

[4] Law No.21/2001 Article 33 verse 3a and 3b on Fund Balance of Papua Otsus.

[5] Papua Public Expenditure Analysis: Regional Finance and Service Delivery in Indonesia’s Most Remote

Region, World Bank, 2005.

[7] Evaluasi Otsus Papua dan Papua Barat: Refleksi Sebelas Tahun Pelaksanaan UU No 21 tahun 2001, Ditjen

Otoda Kemdagri, Kerjasama Kemdagri, Lembaga Administrasi Negara, dan Partnership for Governance

Reform, 2012, hal. 95.