Poverty and mines sound like two opposites. If managed properly, the extractive sector will be very lukratif, as evidenced by the fact that the companies that have the largest profits in Indonesia are mining or oil and gas businesses.

Unfortunately, poverty and mining often come together. As the Government of Joko Widodo began to vigorously campaign for the success of the downstream policy,public attention to the mining sector increased. Reports emerging from downstream central locations responding to this public concern contradict the fantastic growth figures of these provinces. The percentage of poor people in the three main nickel downstream provinces actually increased between 2022-2023 (Kompas, 2023a). President Joko Widodo himself did not reject these findings (Kompas, 2023b).

Similar trends can be found in four mining-rich districts, West Aceh, Lebong, Bojonegoro, and West Sumbawa, which are PATTIRO’s working areas. Mines contribute significantly to the economies of these four regions, and some of them are even dependent on Mines. In Bojonegoro Regency in 2023, take it, the contribution of the oil and gas extractive sector to Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) reached 49 percent. In West Sumbawa Regency, the figure dramatically reached 82 percent. In West Aceh and Lebong, the contribution of mining and oil and gas is smaller, namely 25 percent and 4 percent but still significant. However, the percentage of poor people in these four regions is higher than the percentage of the National poor. In 2023, the percentage of the National poor population will be 9.36 percent, while the average poor population in these four regions will reach 13.53 percent.

This inequality reminds us of the phenomenon of natural resource curses that occur in many places, especially developing countries. Economists identify that the abundance of Natural Resources in these places tends to be inversely proportional to the well-being of the population (Karabegović, 2009; Harmela & Gregow, 2011). Although Indonesia is said not to experience the Curse of natural resources nationally (Rosser, 2004), the situation is different at the regional level.

Analysis of Rahma et al. (2021) shows a clear link between dependence on Natural Resources and stagnant sustainable development in 33 provinces. Rahma et al. assess sustainable development in the region from economic growth, Open unemployment rate, poverty rate, Human Development Index, income inequality and Environmental Quality Index, while the dependence of the region on natural resources from revenues from natural resources per capita and GDP per capita. Rahma et al. measure the relationship between these two variables. As a result, provinces that depend on natural resources such as East Kalimantan, West Papua, Papua, Riau and Aceh tend to have low levels of sustainable development.

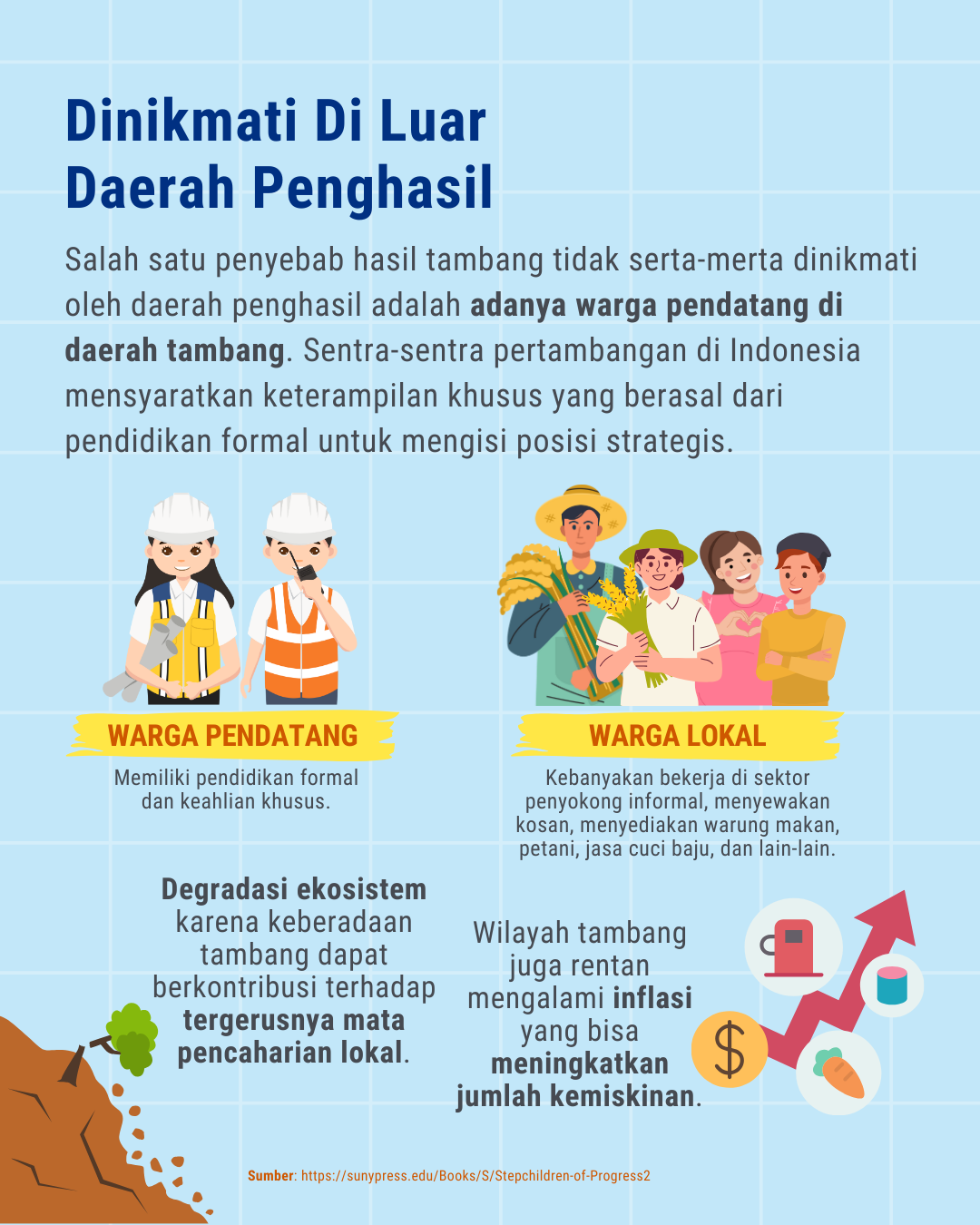

Enjoy the outdoors

Study Rahma et al. interesting because it complements the economic analysis that explains The Curse of Natural Resources does not occur in Indonesia nationally. If meaningful growth persists at the national level thanks to the extractive sector, the picture presented by Rahma et al. tells us that the results of mining are more enjoyed outside than inside the producing area itself. To explain why this happens, we can first look at the large number of workers from outside the region in the mining sector.

We certainly do not have the same complete mine worker profile data. But, if we look at the percentage of poor people in the provinces of Aceh, Bengkulu, East Java and West Nusa Tenggara, the lowest percentage of poor people is always in the cities. Mining center districts such as the four districts mentioned have a percentage of poor people who are not far adrift from other districts.

In 2023, Bojonegoro has a percentage of the poor population of 12.21 percent. This figure is not far off when compared with the average percentage of poor residents of districts in East Java which is at 11.76 percent. But, as soon as we compare with cities in East Java, whose average poor population is only 5.69 percent, the inequality is immediately striking. In the same year, West Sumbawa had a poor population percentage of 12.95 percent, relatively better than the average figure of all NTB districts at 15.23 percent. However, this figure is lame compared to the percentage of poverty in NTB cities which averages 8.64 percent.

Thus, we can say that there is an accumulation of wealth in urban areas. While workers with the formal education or specific work experience required by the mine live in the city, locals can only work as manual laborers or in support sectors such as restaurants, workshops, boarding houses, or laundry services (Robinson, 1986). on the other hand, high inflation occurs in mining areas. Inflation causes prices to rise and the number of poor people to increase. The presence of Mines also causes pollution, ecosystem degradation and, not infrequently, land grabbing. That is, it has the potential to eliminate traditional local sources of livelihood.

This situation confirms to us the need for a pro-equitable policy in relation to the distribution of Natural Resources. The districts of PATTIRO working area have abundant mining resources. Although it has not been explored as much as in other districts, West Aceh district has deposits of iron ore, gold, Western stone, zircon sand, and galena. The area through which the Bukit Barisan Mountains pass is a rich mineralization area. Lebong Regency has gold, coal, and copper mining potential.

Meanwhile, West Sumbawa Regency has the Batu Hijau mine, the second largest copper and gold mine in Indonesia. The prospect of copper and gold concessions can still be explored further. So, Bojonegoro is one of the largest oil and gas producing areas in Indonesia. If managed properly, mining communities in these districts should be able to live in prosperity.

Need DBH optimization and more progressive ADD allocation

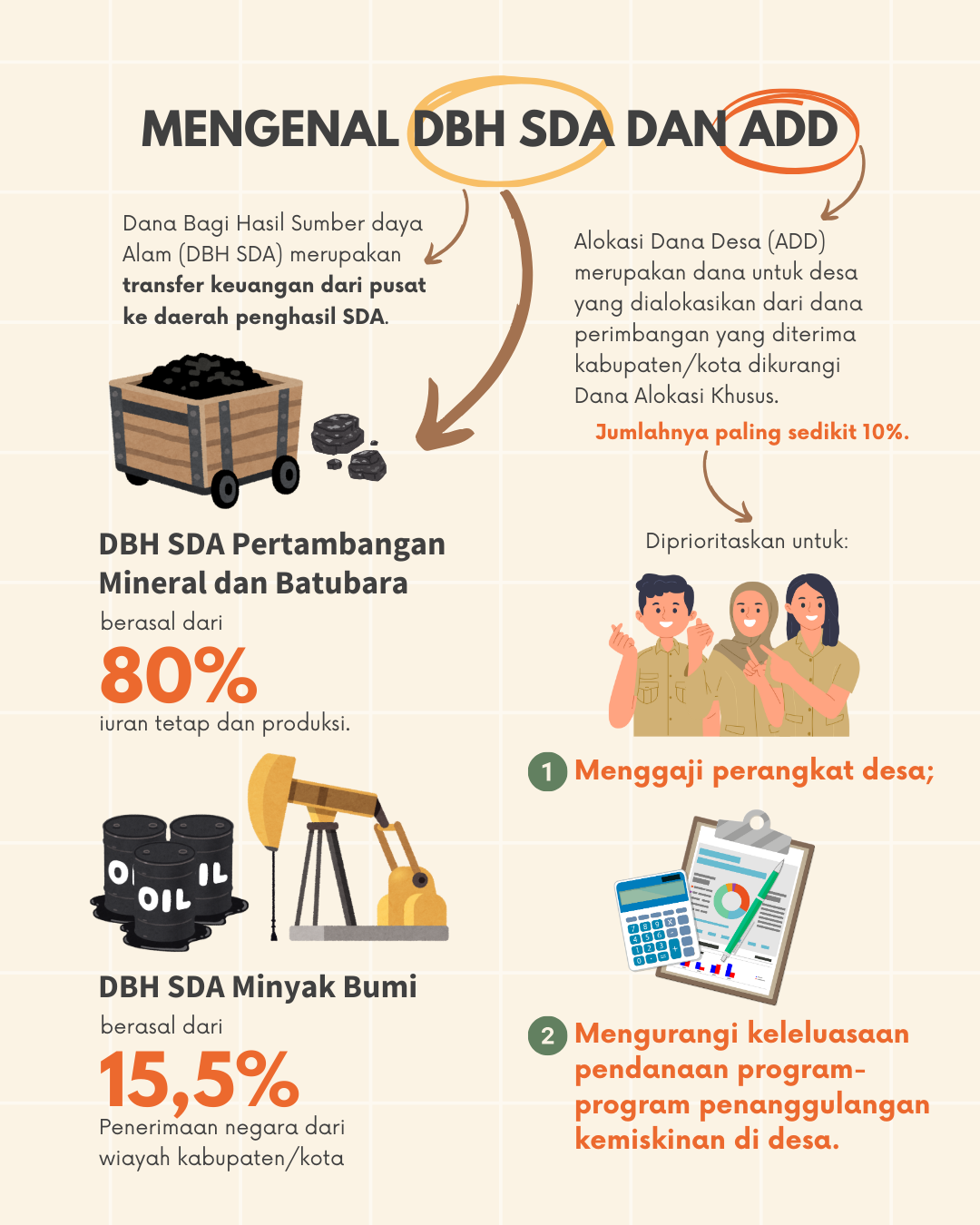

If we examine, the philosophy of equity has actually inspired existing policies related to mining revenue sharing. Natural resource producing regions get financial transfers from the center through the Revenue Sharing Fund (DBH). DBH SDA for mineral and coal mining comes from 80 percent of fixed dues and production dues, while DBH SDA for Petroleum comes from 15.5 percent of state revenue for petroleum mining SDA from the district/city concerned and for the province, 15.5 percent of state revenue for petroleum mining SDA from the province concerned.

In some cases, the contribution of DBH SDA is large enough to contribute between 40-60 percent of the APBD. In Bojonegoro, the realization of DBH SDA Migas from 2017-2023 is almost always above 40 percent. In 2020, its contribution only reached 26.9 percent but we know that in that year the price of Petroleum plummeted due to the covid-19 outbreak. In West Sumbawa, transfer funds from DBH Pajak and SDA accounted for 85 percent of total regional revenue. However, the high poverty rate in these areas indicates the need for more progressive optimization of DBH SDA in order to be directly accepted by the mining centers themselves. Meanwhile, the comparison of DBH SDA contributions in 2023 to the Lebong APBD reached 3 percent and in West Aceh reached 7 percent.

Direct-to-village fiscal incentive policies demonstrate effectiveness in tackling poverty. Village Fund policy, let’s call it, an example(Bukhari, 2021; Sigit & Kosasih, 2020; Sari & Abdullah, 2017). In villages, this policy often translates into the construction of physical facilities. Although this orientation to physical facilities is often criticized, in fact it absorbs labor at the village level. In many cases, it is also used by residents to build agricultural roads, making it easier for residents to use or open agricultural land.

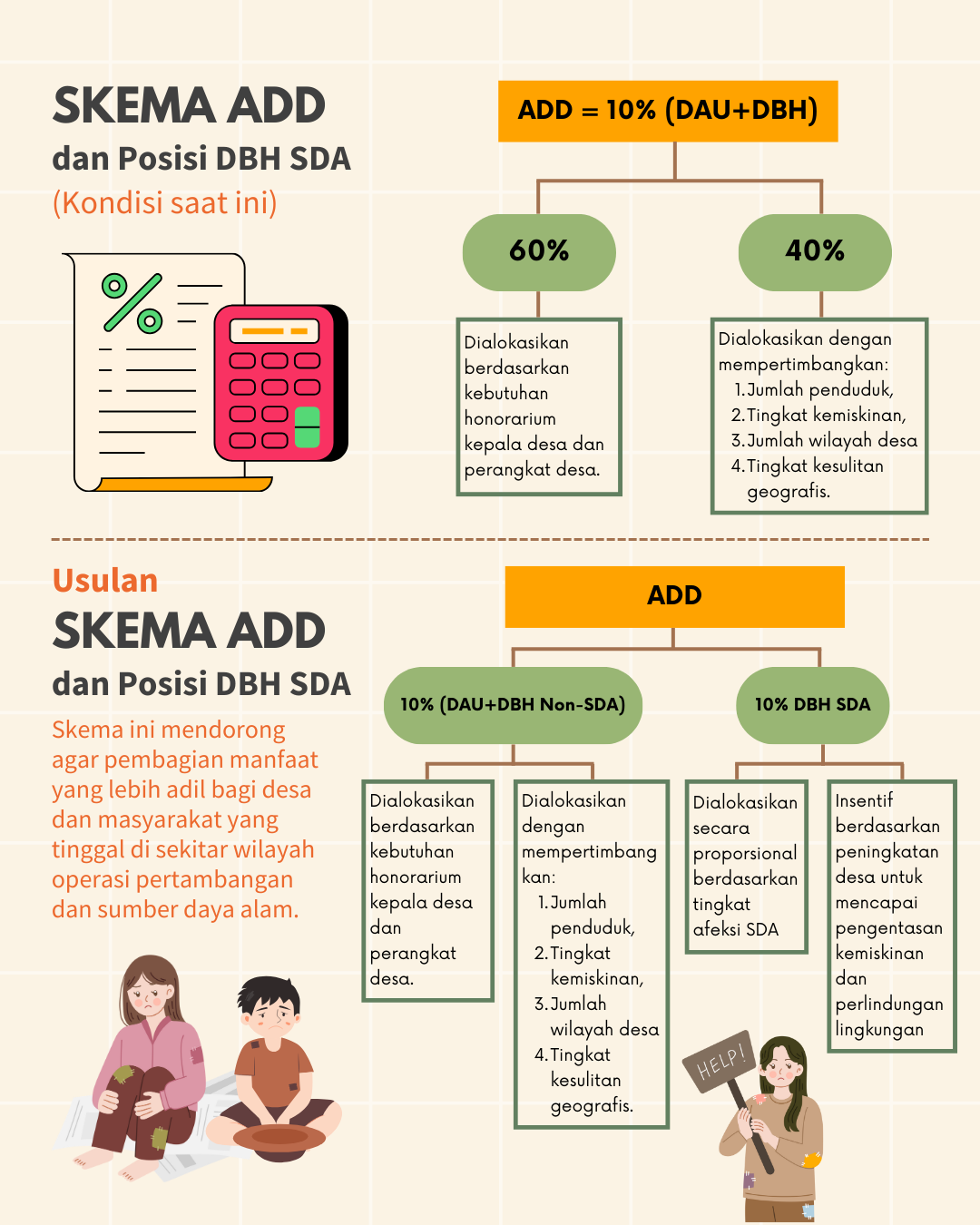

Currently, the village law of 2014 has mandated the allocation of village funds (ADD) of at least 10 percent of the balance funds received. In many regions, local regulations stipulate that this 10 percent allocation is prioritized for fixed income or to be the salary of village officials. Even so, the 10 percent figure is actually the “least”allocation. Thus, although ADD is currently limited and in most cases used up for village payroll, regions still have the flexibility to develop ADD schemes that support poverty reduction. In addition, the large contribution of DBH SDA to regional expenditure and revenue shows that there is fiscal space that can be utilized to enlarge ADD.

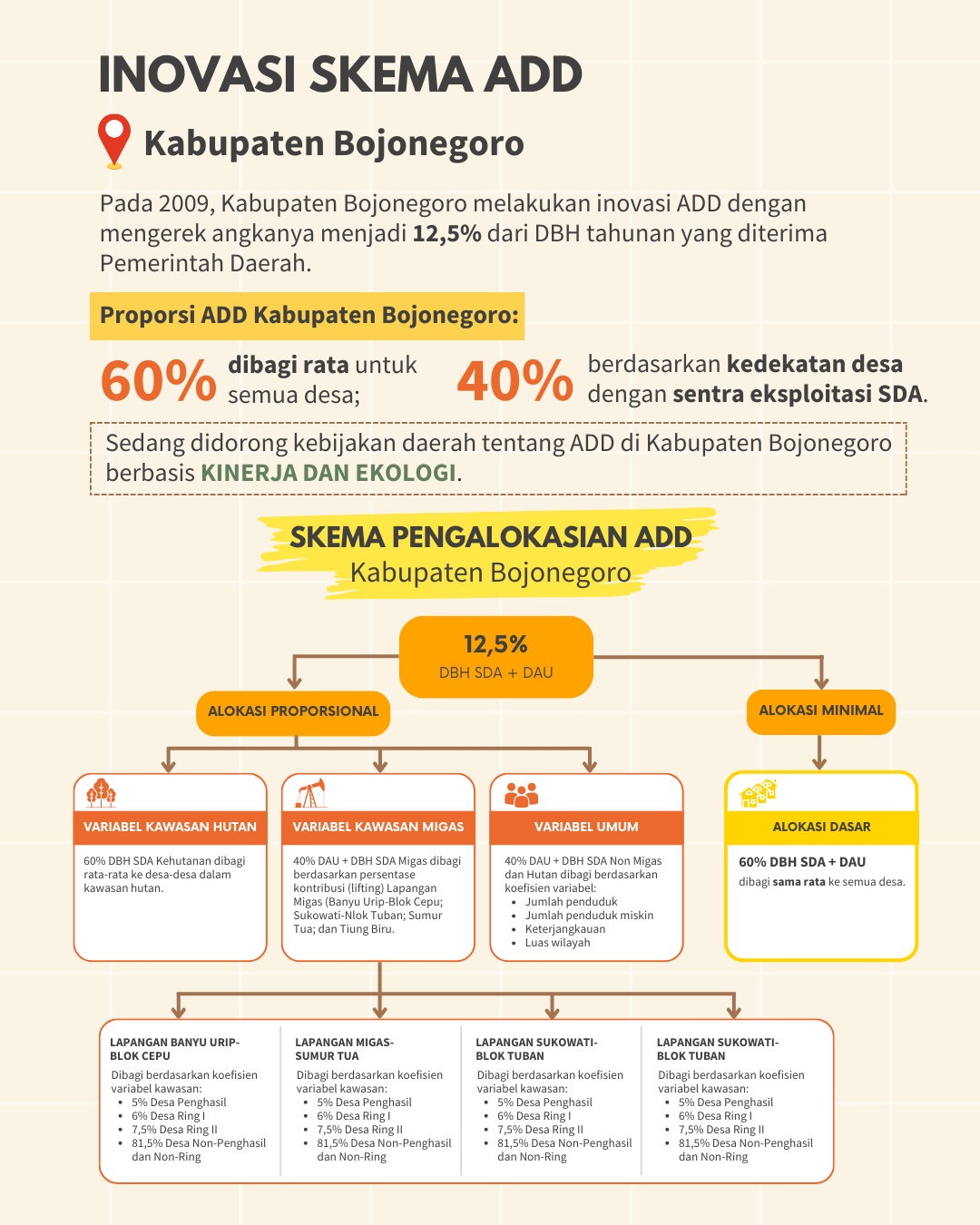

In 2009, Bojonegoro innovated ADD by hoisting the figure to 12.5 percent of the annual DBH received by the Regional Government. Of all ADD, 60 percent is divided equally in all villages and 40 percent is based on the proximity of the village to the center of exploitation of Natural Resources. In 2023,the ADD ceiling of Mojodelik Village, which is a natural resource producing village, will reach Rp2.85 billion,the largest in Bojonegoro regency, while Gayam Village, which is a ring 1 village in the oil and gas area, will have an ADD ceiling of Rp2. 92 billion, the second largest in the Regency.

What is done by Bojonegoro Regency needs to be appreciated. The problem of poverty inherent in Bojonegoro Regency for a long time, can not be separated from factors such as floods and droughts that occur every year a poor irrigation system, and corrupt bureaucracy. Thus, although Bojonegoro Regency still has not reached the expected percentage of poor people, the district’s journey to overcome poverty is a process and needs to be supported. The development of poverty rates from 2004-2022 also showed a dramatic decline.

Currently, in other districts, PATTIRO’s working area is also being encouraged by more innovative poverty reduction funding policies, both by encouraging the reformulation of ADD and by realizing better communication between companies, governments, and residents of mining circles. In West Sumbawa Regency, the district government, village government, civil society organizations, and universities are working together in formulating ADD from DBH SDA by including poverty reduction performance indicators.

In Lebong, ADD still cannot be encouraged to be allocated to mining-producing villages because of the low fiscal capacity of the district government, as well as in West Aceh. However, in West Aceh, the Corporate Social Responsibility Forum (Tjslp) is now facilitating communication between the company and the mining community and the CSR program is getting more intimate. Elements of universities are involved to oversee CSR programs and help identify community livelihoods.

While this kind of regional initiative is very important, at the same time there is a need for policies at the national level to accelerate DBH SDA revenues. The central government needs to realize that poverty in mining pockets is not only an ordinary problem but also an irony. The public will wonder why the government is constantly raising the extractive sector while the areas that produce it are far from prosperous. The public will easily remember it as the phenomenon of dead rats in rice barns.

Public support for extractive policies will be largely determined by the extent to which the government can prosper producing regions, not just those in urban economic centers. The government’s alignments need to be shown with concrete evidence, namely fiscal alignments.