![]()

by: Ahmad Rofik (Program Development Unit)

Openness of Public Information in Indonesia

Implementation of Law no. 14 of 2008 concerning Public Information Openness (KIP) has been in place for four years. The average achievement of basic compliance for the formation of Information and Documentation Management Officers (PPID) has only reached 48.27%.[1] This low achievement is not unique to the government regions, especially districts which have only reached 170 out of 399 districts (42.61%), but also in state institutions at the Ministry/LSN/LPP level which have only reached 41 out of 129 institutions (31.78%). In fact, the formation of PPID in public bodies is only the initial stage of efforts to realize transparency in state administration.

PATTIRO’s experience in managing the Community Access to Information (CATI) program shows that there are three types of benefits from implementing the KIP Law for the community, namely: (a) ease of accessing public information [2], (b) the community benefits from improvements in public services [3], (c) preventing irregular practices and corruption in the delivery of public services.[4]

Change at the Community Level

In strengthening the transparency system, PATTIRO also focuses on ensuring that the public can benefit from access to information. Strengthening community groups through community organizing known as community centers or CCs was chosen as a strategy to put pressure on public bodies (state affairs administrators) to be transparent regarding the information they control.

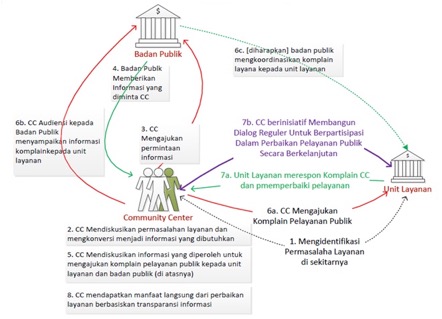

The CC capability improvement stage includes several levels, namely (a) CC is able to identify service problems in the area to be converted into the type of information needed; (b) CC is able to submit requests for information; (c) CC obtains the requested information and discusses it into material for advocacy (and other follow-up actions); (d) CC submits a complaint/proposal for improving public services to the service unit, as well as conveying complaint information to public bodies or converting it into direct benefits; (e) CC takes the initiative to build regular dialogue with service providers. In simple terms, the milestones/stages are as in the following scheme.

Changes at the Service Provider Level

Another lesson related to the effectiveness of the function of Information and Documentation Management Officers (PPID), is influenced by a number of factors, including: (a) commitment of regional leaders, (b) capacity of PPID in understanding laws and regulations related to KIP, (c) skills of PPID in managing and serving request for public information, (d) support for supporting facilities for the management and service of public information.

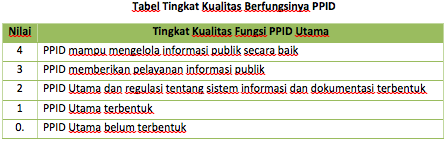

At the level of PPID functioning, the CATI program provides direct assistance to PPID in the information management and service process. Assistance is carried out intensively and independently by CATI PATTIRO program staff in each region. In carrying out this assistance, the level of PPID functioning is simply categorized according to four levels, namely: (0) Main PPID has not been formed; (1) Main PPID is formed but has not yet drafted regulations; (2) PPID was formed and has prepared regulations regarding information and documentation systems; (3) PPID provides public information services; (4) PPID is able to manage public information well, following table.

Along with the development of information technology in state management which correlates with the relationship between the state and society, information is also positioned as a public good, especially information related to services that concern the lives of many people. This approach, known as the economic regime, believes that providing access to information is a prerequisite for achieving a more efficient allocation of public resources and closer to the needs of society. The provision of systems and infrastructure known as Open Data has provided access to data without having to go through a request process first. Data obtained in the mass version can be reprocessed by users so that it inspires local communities to develop their initiatives to improve the quality of public services through collaborative schemes.

ICT for Transparency

Learning with local governments in managing PPID has also inspired PATTIRO to develop the PPID Public Information System (SIP) application which has been implemented in NTB Province, East Java Province, Malang Regency, Southwest Sumba, Ngada, North Central Timor and also at the national level in Ministry of Internal Affairs. Through this application, requests for information can be made online, saving time and costs. The public can directly access information that has been declared open in the Public Information List (DIP). Regional governments also experience the benefits of easier, more economical and efficient information management and public information services. Document management is integrated with information services both offline and online, automatic updating of the Public Information List (DIP), data connectivity between Regional Work Units (SKPD: departments/offices/agencies), automatic creation of recap reports, and connection with the reporting system information services with the Ministry of Home Affairs.

The direction of accelerating the implementation of the KIP Law in regional governments is also supported by the central government which has direct links, including the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Ministry of Communication and Information, the Central Information Commission, and the Presidential Work Unit for Development Monitoring and Control (UKP4). At a certain level, UKP4 has a more intensive level of influence on ministries and central government institutions. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Home Affairs is quite intensive in pushing for the implementation of regulations in local governments.

Information Disclosure and Open Government Partnership

The involvement of civil society at the national level has leveraged transparency practices in Indonesia in the global OGP initiative. In 2012, the Open Budget Index (OBI) Survey ranked Indonesia second in Asia after South Korea in transparency of state financial documents. Even though we have succeeded in achieving a high level of transparency, this does not have a direct impact on improving the anti-corruption index. The anti-corruption scheme is actually built through a logical framework of collaborative public participation by citizens and the private sector in the administration of state affairs. This collaborative participation does not only stop at accommodating aspirations in decision making, but also extends to the implementation and monitoring of development through collaborative involvement of the resources between these parties.

It must be acknowledged that the open government structure envisioned by the global OGP initiative is only at an early stage. Resistance from civil society, especially regarding equality of involvement (participation), emerged in the early days. Even in Indonesia’s OGP agendas, the positions of government and civil society are still not balanced. Some groups even view OGP as more of open data, even though it is only one of the infrastructures for creating an open government. In its development, this resistance began to give way to a sense of shared ownership of Indonesia’s OGP agenda.

Indonesia also has not found this OGP pattern at the sub-national level (province/regency/city). OGP should be a lever for the creation of open government which has an impact on efforts to improve public services to increase welfare. Innovation efforts must be fostered both in the central government and regional governments. It is also important for these innovations to be replicated and scaled up both at the national and international levels.

[1] Source: Dit. Komunikasi Publik – Ditjen IKP, 23 September 2014.

[2] Implementation of the Information System application for Information and Documentation Management Officials in NTB Province (http://ntbprov.sip-ppid.net/index.php/document), Ministry of Internal Affairs (http://ppid.kemendagri.go.id/document)

[3] Experience at the Manokwari Regency Health Center. The West Lombok education office also accommodated CC’s proposal regarding handling poor students who dropped out of school, that poor students who dropped out of school could continue their education because in the new 2014 school year they received additional pocket money of Rp. 1,000,000,- per student per year.

[4] CC Flotim Regency successfully advocated for the Poor Student Assistance (BSM) funds that were deducted at SD Inpres Lewoneda, Kemutu Village, Ile Mandiri District, to be returned to the students concerned. Previously, BSM funds were deducted by schools and would be used for administration costs, equalization of other students who did not receive BSM, school committee fees and uniforms. Apart from canceling BSM cuts, there is also a commitment from the school regarding more transparent management of BSM funds. This change in behavior mainly results from CC’s awareness of interacting with service units.